Last year, my team started noticing a trend: Employer after employer would see talent shortages in the same areas — data analysis, software engineering, marketing, finance, cybersecurity, product management and a handful of others.

It’s not until my team started looking at the data across employers that we started to get a sense of what the problem was — and, no, it wasn’t a shortage of people who had reskilled into that area. There are tens of thousands of folks skilling into these areas every year. The problem was a shortage of the “right kind” of jobs.

When many of us think about the distribution of talent in our organizations, we imagine it a bit like a pyramid. The majority of our workforce is in non-exempt roles, with fewer roles as you climb more senior in the organization. That’s especially true for certain parts of an organization, such as Field and Operations type functions.

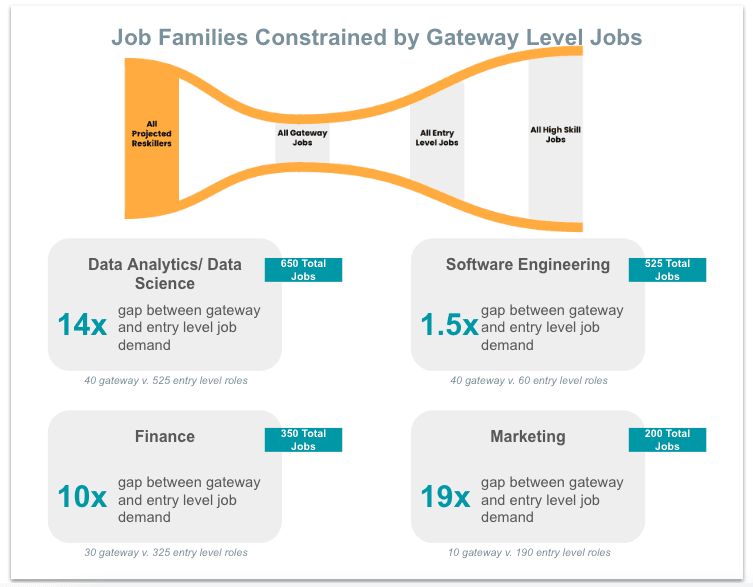

It wasn’t until I led my organization’s research on career mobility last year that I realized a “pyramid” isn’t the shape of talent in some of the areas of highest demand. In the data across company after company, we found that the talent distribution profile of many organizations looks more like a distorted hourglass. Many organizations contain a heavy concentration of front-line roles at the bottom and heavy concentration of individual contributor roles toward the top of high demand areas (e.g. Senior Cyber Security Specialist or Senior Software engineer). Then there’s a tight funnel between the two extremes. This matters because 63 percent of American workers last year left their jobs because there was no opportunity for advancement.

In a recent talent intelligence exercise for an employer partner, Guild found a 10x gap between roles in at least four different areas of highest demand in their organization: finance, HR, marketing and data analytics.

With such a tight bottleneck for their talent pipeline and a tight market from which to hire externally, an employer faces two challenges. They bleed away employees who are getting hired away as they reskill and they have difficulty hiring their own qualified talent after they reskill. It’s a clear signal to revisit the entire architecture of the roles and take bold steps to drive talent retention and prepare a talent pipeline for the future. In fact, companies with low internal mobility have an average employee tenure of 2.9 years, while companies with high internal mobility have an average tenure of 5.4 years.

Do yourself a favor: Look at your job postings in some of the most critical job families in your organization right now. Do you find more data analyst IVs or data analyst Is? What about software engineering jobs, are there more junior level jobs or senior level? How many entry level marketing jobs do you have in comparison to senior level marketing positions? If you’re like the employers I’ve worked with, you’re missing the stepping stones that would enable your existing talent to become the talent you need in the future.

Designing the gateway

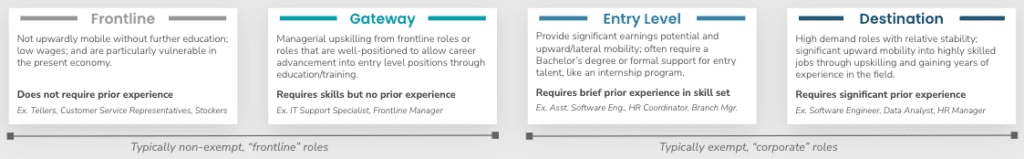

Let’s align on some terminology.

Gateway jobs are positions that don’t necessarily require degrees, but do develop the kinds of durable and transferrable skills needed in many exempt roles. They might include call center managers who are responsible for managing to dashboards or IT help desk professionals who are troubleshooting systems and network challenges alongside users.

Then there are “entry level” type roles, such as “data analyst I” or “associate software engineer.” In the same job families as entry-level, you usually find roles such as “data analyst IV” or “senior software engineer” — these are destination roles.

I’ve found lots of misalignment in terminology across companies in these areas — some call these roles “entry level,” others call them “gateway,” and others call them “early career.” Regardless of the name, the most important part of the job posting is how many years of experience are required: < 1 year, preferably accepting classwork or bootcamps as example of the necessary experience.

Today, we find ourselves in a talent crisis. Crises require reevaluating understood norms, processes and systems. We must be willing to ask ourselves — “is our talent shortage a mess of our own making?”

Without realizing it, have we constructed a job architecture that constrains entry level jobs to our small class of “campus recruits” each year? And also one that ignores the talent in our own front lines willing to reskill and meet our talent needs, if only we’d rethink how we divide and construct our work? Instead of posting for software engineer I or a data analyst I and developing talent, hiring managers post roles for software engineer III or data analyst IV, which require five to seven years of experience or more. There needs to be a balance if the focus is on internal development.

Increasingly, this is a matter of equity.

In conversations with HR leaders at Fortune 100 companies, a common theme is seeing internal mobility as a critical lever in creating more opportunities for historically marginalized talent in their companies. Those conversations happened across retail, travel and hospitality, healthcare, and entertainment industries.

Revisiting our job construction and our talent bottlenecks is a critical step in creating more equity. For one of Guild’s employer partners, they cite their education benefits as a source of creating equity, with promotion likelihood higher by 87.5 percent for black employees participating and for 70.7 percent of Hispanic or Latino employees participating.

This theme around equity in talent development and career management is a recurring theme in Josh Bersin’s latest report: “Growth in the Flow of Work.” In the report, Bersin’s team calls on HR departments to articulate “career pathways” where they enable movement of individuals through skill adjacencies and allow them to move to more valued, in-demand careers.

Beyond the equitable talent development philosophy, they’re opening roles for their own reskilled talent, recognizing the return on investment they get immediately through retention and engagement of existing talent they’ll get if their employees believe there will be future opportunities for them.

In McLean & Company’s Talent Marketplace report, they cite that employees who agree or strongly agree that they can advance their career in their current organization are 3.4x more likely to be engaged compared to those who disagree or strongly disagree. In addition, when they create their own future talent pipeline through these programs, they only further compound the ROI of the investment by reducing recruiting costs.

The talent bottleneck

According to Gartner, one in three candidates who applied to jobs in the past year first searched internally within their organization before pursuing external jobs. Reskillers are facing a severe bottleneck and it’s in the areas their companies are in greatest demand to hire good talent into. It’s like we’re in some weird corporate talent Twilight Zone episode where our long-established rules and culture fail to allow us to see the talent we have in our own companies. As we look at the trends of talent constraint in these job fields that are projected to continue for the next seven to 10 years, it seems we won’t be getting out of this twilight zone for years to come.

At Guild Education, we have a dedicated team called the Career Mobility Center of Excellence that works with numerous employers who are reskilling their frontline employees through boot camps and full degree programs. Even if those employees are exempt workers and are fortunate enough to work in an organization with a talent marketplace that enables stretch projects, they still don’t satisfy the requirements of the actual job postings. In some instances, these employees quit to go find other companies that have the infrastructure to help them close their experience gaps. They know that if they stay in their own organizations, they will languish in their existing roles without opportunities to apply the new skills they’ve acquired inside the very company that helped them reskill.

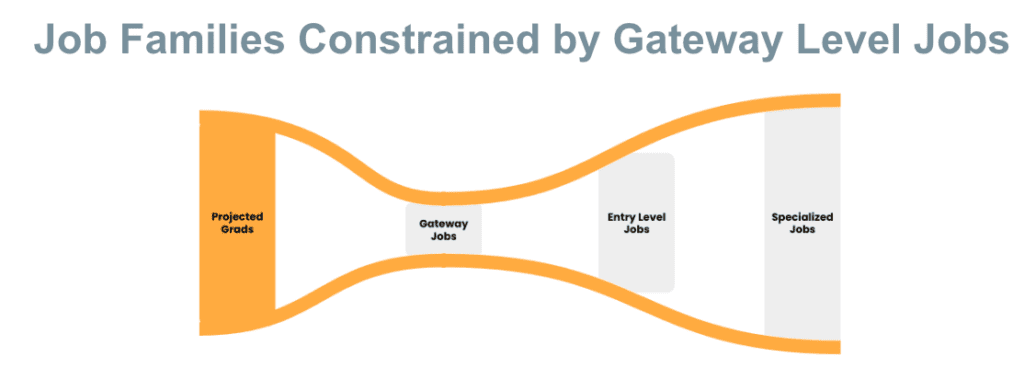

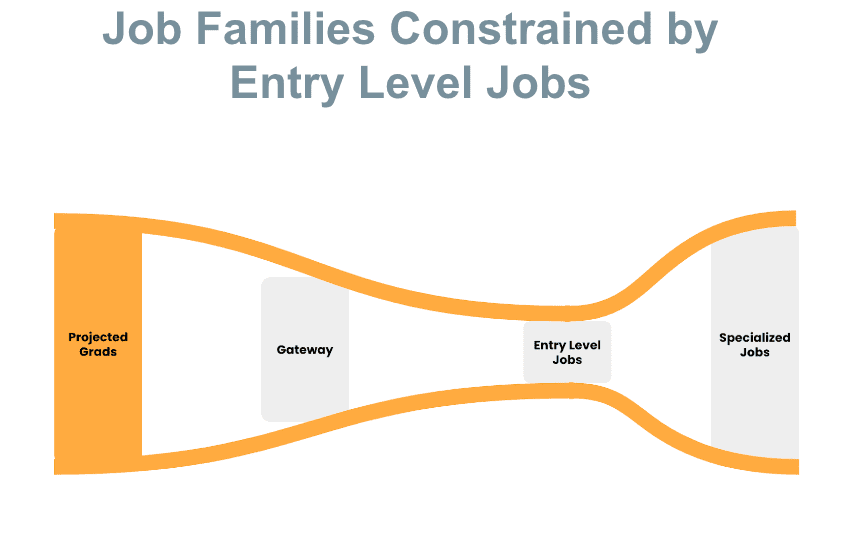

To illustrate this scenario, we created a visual to help employers see the significant gap between their source talent that’s reskilling and their high demand roles. This talent intelligence exercise makes clear the work that an employer must do to ensure their reskillers have an opportunity within their own company. We call it the bottleneck analysis.

Here are two of the most common problems we find: constraint in gateway jobs and constraint in entry-level jobs.

Constraint in gateway jobs

In this situation, advancing opportunities for frontline talent is limited because there’s no role in which these employees can develop many of the communication, problem solving and project-based working skills most valued in exempt roles.

Most frontline reskillers would have to target higher-level roles and jump more levels and across the organization (that typically require bachelor’s degrees and/or relevant experience) to gain upward mobility. This limits the opportunities for frontline graduates of certificate or boot camp programs or even new degree holders with limited relevant experience. A constraint in gateway jobs presents a high level of risk that makes internal mobility for the frontline nearly unachievable.

Two actions you might take to address this issue:

- Consider lowering inflated entry-level job requirements, offering more “equivalencies” around experience and education OR opening junior-level roles to create more opportunities for frontline advancement that bypasses gateway jobs.

- Consider identifying other business units with higher volumes of gateway roles that could contain transferable skills and create pipelines to these adjacent roles to build a stronger and more cohesive business strategy across units.

Constraint in entry-level jobs

In this scenario, opportunities for frontline talent to grow into gateway roles exists, but advancement becomes increasingly competitive when moving into entry-level salaried roles in new job families. Employees who are looking for more money or flexibility may begin to look elsewhere for upward mobility, despite the company having such a high need for more advanced and specialized talent in the same areas that folks are actively reskilling into.

What are the actions you might take to address this issue:

- Consider strategies to upskill and move entry-level talent into higher-demand roles more quickly through projects and talent management practices. This will free up more openings at the entry-level to be filled by frontline graduates.

- Consider movements into other job families with high levels of skill adjacencies to the end destination roles.

- Revisit tasks of specialized roles to consider what can move below the line to entry level jobs.

Revisiting expectations

Here’s the mandate of everyone reading this article: We must do everything we can to open more roles with lower experience requirements. And we must invest in developing our own talent. It drives employee engagement and retention today, while building a talent pipeline for the future.

The HR function can help business leaders see that they’re unlikely to ever hire their way out of their talent shortage. Doing so pushes wages to an unsustainable level in a concentrated set of job families as you look for talent that doesn’t exist, meanwhile organizations would be likely to bleed existing talent due to overwork and frustration with not getting the opportunities needed.

We need to exit this never-ending merry-go-round and make the strategic decision to convince the business to fund additional “entry level” roles in this field to begin the process of building some of its own talent. This would result in us seeing the acquisition of talent as the same capital investment we make for our property and equipment.

In the end, if your organization deploys a talent marketplace without revisiting the organizational friction that comes in literally not having gateway jobs to transition, intentionally designed projects to build skills, or entry level jobs with low experience requirements, the opportunities to build talent will be lost and the value of the platform largely unrecognized.

We all know that revisiting job architecture is far easier said than done, but desperate times call for desperate measures, and our current talent shortages are desperate times.