The term “soft skills” is often met with an eye-roll these days. It is regularly delivered with air quotes to acknowledge that most of us have come to hate the expression. There’s a distinction to be made between broad types of skills, to be sure. But the hard/soft distinction doesn’t quite fit. Never mind that the so-called soft skills are actually the hard ones — they are more challenging to obtain and require a deeper and more enduring commitment. Some organizations have kept the same simple bifurcation in their skills frameworks but rebranded soft skills as “human skills” or “power skills.” This doesn’t hit the mark either; even the most human of skills are dependent on some form of digital delivery, and technical skills without human context are a recipe for failure in a world where empathy has become more critical than ever.

Tim Brown of IDEO popularized the concept of T-shaped talent, and most organizations have bought in. As the prevailing wisdom has held, it is important to develop skills in a T-shape, with a horizontal continuum of “soft” or human skills that intersects with deep expertise in a specific area. This T-shaped framework made perfect sense in earlier generations, when employees spent their entire work lives at one or two companies. But career trajectories have become more fluid, with more frequent shifts from one job or career to the next. Add to that the unrelenting evolution of technology tools, and the T-shaped model of skill development in only one technical area seems even less useful now as any technical specialty likely has its own shelf life.

In reality, these seemingly perpendicular categories are deeply intertwined. One of the best software engineers I ever managed could code her way out of any scenario. But I knew I couldn’t send her into any meeting without someone to serve as her translator and message-softener. Her survival in the organization grew more tenuous over time as dynamic client interactions became increasingly important. I also had emotionally connected, communicative employees who simply couldn’t keep up with their more technically minded counterparts. It’s not that their roles were overwhelmingly technical, but they required openness to developing key workplace tech skills. Without a commitment to upskilling, and in a way that addresses the complex interrelationship between skill types, employees like these experience alienation, frustration and perhaps even pressure to leave the organization.

The growing interdependence of human and technical skills is not the only factor that demands new skill-development frameworks. Research suggests that skills generally have a “half-life” of about five years, with the more technical skills at just two and a half years. This results in something that might resemble “E-shaped” talent, or, eventually, a base with new technical skills constantly being built, but also losing relevance in time. Business leaders and learners need a completely new model for thinking about skills, a model that fosters thinking about emerging questions:

- Are skills more durable or more perishable?

- Are skills transferable across roles, job families or industries?

- Are skills in demand, and will they be so in the future?

Planning for long-term needs

Before launching a talent-development initiative, it’s important to consider just how transferable a given set of skills really are. Do they enable horizontal or vertical movement of talent within the organization? Or are we creating dead-end jobs that will result in disengagement and frustration? Organizations like Emsi and Burning Glass have done a great job of mapping skills adjacencies or “clusters.” For example, project management doesn’t stand on its own. It’s tied to project schedules, work planning, stakeholder management, governance, and project management platforms like Microsoft Project, Asana or Jira. These help us visualize related skills and related roles so that talent can flex quickly to meet changing business demands.

The next factor to consider is just how long these skills will matter. To illustrate, let’s divide skill durability into three categories: perishable skills (half-life of less than two and a half years), semi-durable skills (half-life of two and a half to seven and a half years), and durable skills (half-life of more than seven and a half years).

What kinds of skills fall into that perishable bucket? Tech skills, especially those related to specific vendors, platforms or programming languages that are updated frequently. Organization-specific policies and tools are also highly perishable — they frequently shift due to transformation initiatives and changing organizational leadership or philosophy. Another cache of perishable skills is found in the specialized processes an individual team puts in place: intake, prioritization, procurement, customer support and even data gathering. Each of these is dependent on the very fluid tools, organizational structures, software and team dynamics in which those processes exist.

Semi-durable skills tend to be those frameworks that are based on understandings that may remain relevant for a few years. Every field has frameworks like these, base sets of knowledge from which field-specific technologies, processes and tools arise. They are longer-lasting and more important than the perishable skills, but are still likely to be replaced as the field grows, expands and evolves. In the learning and talent development field, these would include the ADDIE process used for designing and developing learning content, or the various learning theories that may have currency today, but are likely to change as learning science advances and businesses pivot their strategy and approach.

Durable skills constitute a base layer of mindsets and dispositions. These skills aren’t just “ways of thinking”; they are tangible, teachable and measurable. They include skills like design thinking, project management practices, effective communication and leading others. Durable skills have important implications for the effective development and implementation of the array of semi-durable and perishable skills an organization requires. A learning and talent-development professional, for example, possesses a key durable skill: breaking down complex ideas and behaviors to communicate them to others. That skill can be applied in varying contexts, such as in-person instruction, e-learning or video, and can be deployed to relate other semi-durable and perishable skills, such as how to use ADDIE to drive content development or how to use Snagit to create a video.

Building skills from the ground up

If we only train team members for perishable skills, such as how to use the latest version of a platform or how to navigate our newest process, we’re ultimately limiting how effectively our talent can move between roles and job families and how fungible they are through the product changes, mergers and iterations the company might undergo. Current inertia carries us toward spending time and money on training for perishable skills, thanks to the proliferation of vendor- or platform-specific training programs constantly being marketed toward our learners and business leaders. Although it helps the adoption of their platforms, it may not ultimately position our talent and company for long-term success.

The heavy focus on short-term ROI and the delivery of narrow skill sets oft-evangelized in L&D circles may well be the very source of the “skills shortage” industries face today. This approach has created managers who know how to navigate a performance management platform or follow employment law, but ultimately lack the empathy to keep employees engaged and productive.

Approaching training from a durable-skills-first perspective empowers talent to make dynamic, longer-term contributions to an organization. Think through your training strategy from those base durable skills first. For example, if your organization is implementing an Agile transformation, don’t start with training on how to use Jira, Asana or some other work-tracking platform. Likewise, avoid starting at the framework level, because you might be using Scrum this year, Kanban the next, and yet another framework a year or two after that.

Start by training for the dispositions that enable the breaking up of complex work processes into smaller deliverables, checking in with stakeholders and iterating — these are key durable skills. From there, you can layer in training around frameworks, followed by the tools and processes for managing Agile deliverables. Agile delivery is a key skill set for many employee roles today, but it is just one of many. Software engineers will need to also develop durable skills on object-oriented design, while learning professionals need durable skills in user experience design.

A new skills-development metaphor

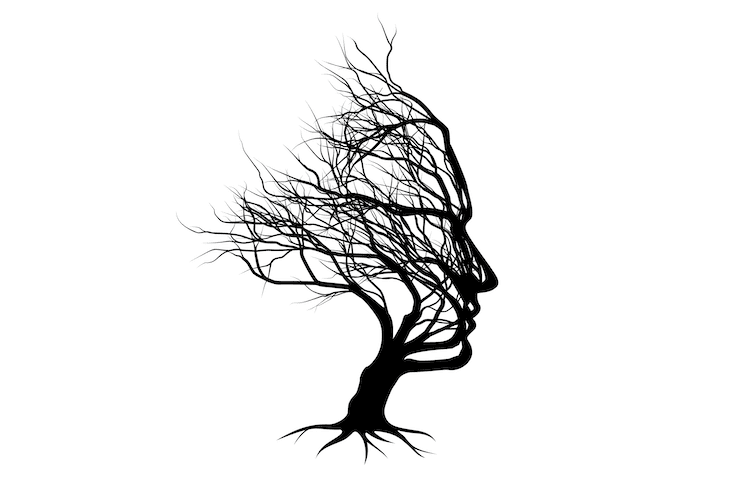

The T-shaped skills development model that accounted for a grounding of soft skills and a deep-dive into a set of hard skills has been more recently modified into an E-shaped model that allowed for multiple levels of deep expertise. But a tree-shaped model may be a more powerful and effective way of thinking through skill development: Durable skills form the roots of the tree, with semi-durable frameworks forming the branches, and more perishable skills coming and going like the leaves with the changing seasons. Our task is to grow a tree that is tall and wide, and flourishes in every season, feeding the roots that keep the tree steady, growing branches of new expertise, and fostering the leaves that change with the passage of time.

When we over-index perishable skills, we handicap our employees from the agility and range they need to respond to an increasingly volatile world. A tree-shaped paradigm enables us to view mindset and framework learning as essential to the task at hand. This organic model represents a different way of thinking about skill development, one that encourages us to develop skills with an eye for their durability, their transferability and their relevance for roles that our organizations may need to fill years into the future.