“In breakout groups, let’s share stories about an embarrassing moment when you said something or did something that you wished you hadn’t. How did you manage that at the time and knowing what you know now about shifting perspectives, what would you do differently?”

That was my pre-Covid morning icebreaker intended to invite vulnerability into our discussions as we started the second day of a workshop I was facilitating made up of American, British and French engineers. I waited through what seemed to be a long period of silence when laughter finally started to fill the room as they shared, in small breakout groups, memories of language errors and other human mistakes.

Seeing that nothing was being shared at the table of French speakers, I walked over to make sure they had understood the intent of the exercise. I repeated how it’s normal to feel anxiety sharing stories of vulnerability and how practicing the skill of perspective-taking can lead to generative dialogs opening the space for sharing novel solutions. One person interrupted me and said: “We don’t make mistakes.” I smiled and said, “Don’t we all, at one time or another, have embarrassing moments in life?”

That evening at dinner, I purposefully sat next to this French engineer. I was curious as to why the icebreaker had fallen flat and why, even during the workshop, their participation seemed limited. It was then that I learned one of the engineers was the French team leader of the acquired company. I silently vowed to observe their interactions and to separate the team the next day, so they could share and learn from others in their global team.

When giving my evaluation of the 3-day workshop to the HR Director and the British VP, I mentioned what I had witnessed. It was brushed off as having been Friday and perhaps it was the intensity of the project the team was working on. Everyone had been under a lot of stress since the merger and had missed two of the 10 project deadlines. I left it at that.

Weeks later, the French team leader’s HR director and business partner asked if I would like to coach the French team leader. That’s what started us on a journey where emotional intelligence, cultural intelligence and psychological safety in teams became the subject of our coaching sessions.

There has been a lot of research over the last two decades around emotional intelligence and cultural intelligence, and less about psychological safety in teams. In this article, I will review how being emotionally and culturally intelligent are vital tools for talent leaders when psychological safety is the solid container for the team’s interactions.

Psychological safety

Psychological safety is not about being nice, politically correct or sweet-talking co-workers. Trust is created between individuals; psychological safety is created in groups and teams. It is a place where you do not fear being humiliated, blamed or ridiculed. It’s about clarity in communication, autonomy, accountability and authenticity; bringing your whole self to your team’s discussions; showing up and speaking up while knowing your input in work-related discussions is recognized and appreciated.

It’s about having a voice, being listened to and feeling included for who you are as a human being. When you know the team and the team leader have your back, you feel comfortable contributing and challenging the status quo. In a psychologically safe work environment, we actively learn from our mistakes and the mistakes of our co-workers.

In the 1965 book, “Personal and Organizational Change Through Group Methods,” Edgar Schein and Warren Bennis first defined this as: “[a workplace] where one can take chances without fear and with sufficient protection.”

Let’s agree that no one cherishes the idea of challenging their boss (creating conflict) or questioning well-embedded ways of doing things (the culture). Yet without the possibility of doing so, we end up frozen or too comfortable with our team where diversity is a given, yet inclusion is not. Learning is stifled and contributions are limited to “yeah saying” or groupthink.

Team projects will stall or fail. Add a dose of global supply chain delays, a global pandemic, remote work stress and emotionally unintelligent leaders or culturally insensitive ones, and you have yourself the perfect storm for what is now referred to as the Great Resignation.

Recent Gallup analysis found 48 percent of America’s working population is actively job searching or watching for opportunities. The data shows it’s less an industry, role or pay issue than it is a workplace issue. So how do we shift that data from employee resignation to employee retention?

Emotional and cultural intelligence

Emotional intelligence, as defined in the book by Marc Brackett, includes the RULER acronym which is: recognize, understand, label, express your own emotional states and regulate, don’t react. This can only be implemented when using self-management and social intelligence (be curious as to what others may be feeling, not assuming you know how others feel) and cultural intelligence which is built on the 4R model, where respect is deep listening which in turn recognizes others’ contributions that leads to building relationships and harvesting the rewards of well-being and well-doing across the complexity of cultural divides.

When these are frequently used tools in a team leader’s toolbox, psychological safety is the sturdy toolbox, the safe container. Candid, open communication where vulnerability is rewarded, not punished is easier said than done. Such behaviors need to be role modeled by the leader and repeated by the team members who acknowledge and accept that, as complex human beings, we all come with scars, scabs, sore spots and stretch marks.

The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety have been defined as:

Stage 1: Inclusion safety, where you feel safe to be yourself and are accepted for who you are, including your unique habits and defining characteristics.

Stage 2: Learner safety, where you feel safe to engage in the learning process – asking questions, giving and receiving feedback, experimenting and making mistakes.

Stage 3: Contributor safety, when you feel safe to use your skills and abilities to make a meaningful contribution.

Stage 4: Challenger safety, when you feel safe to speak up and challenge the status quo when you think there is an opportunity to change or improve.

When team members feel their voice is heard (inclusion safety) and power, rank or prestige does not get in the way of speaking up, they are learning and growing by sharing openly (learner safety). Their contributions and challenging questions are welcomed as part of the perspective sharing that leads to innovation and creativity, especially in these trying times of uncertainty.

Psychological safety is a mutual weaving of emotional intelligence and cultural intelligence into the team’s fabric, so how they work together, learn together and grow together becomes why they stay together. Simple steps to successfully providing the safe space to do this is both in the eye of the beholder (team members) and the holder of the space (team leader).

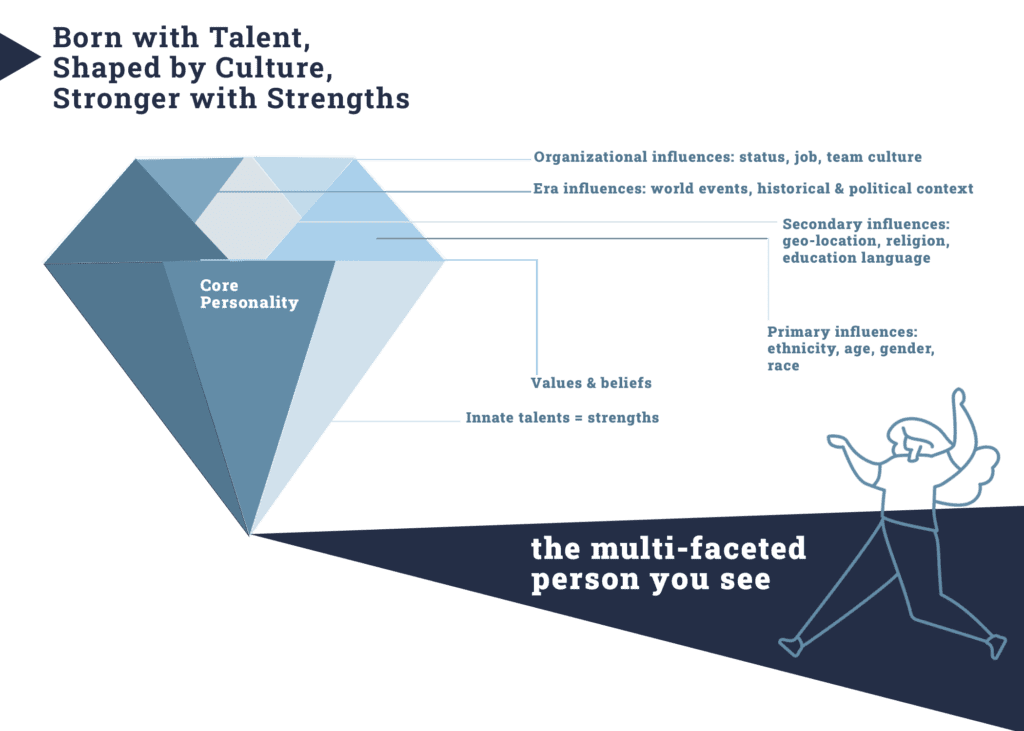

In my coaching opportunity with the French team leader, we first looked at what was strong, not wrong. We are complex beings like a faceted diamond.

My role as his executive coach was to hold the space as he shared his past successes and his values and beliefs. We then collected stakeholder surveys which included difficult feedback. He was prepared for it yet surprised when words of toxicity, not being heard, “having been hired for my head but used for my hands-on approach” were disheartening.

Throughout the coaching sessions, this team leader learned to understand how his beliefs had shaped misunderstood behaviors. He had been at the company for 18 years and was not thrilled at having been acquired by a competitor. In some ways, his internal dialog was about saving face and protecting his team. What did that look like in project reviews? More of a blame game than a “what will we do differently” scenario.

This led to people hunkering down, keeping their heads held high and their mouths closed. A sense of not feeling psychologically safe creeped into the team meetings. It became contagious as the merger became an acquisition. That behavior was palpable during the icebreaker activity: “We don’t make mistakes,” which was said a bit cynically while revealing the shadow side of the team’s culture: Be good soldiers, follow the leader.

With stakeholder buy-in on three behaviors, this team leader wanted to focus on: respect by deep listening, recognizing team member’s contributions and building better relationships. Over six months, I witnessed the team’s transformation from being individual silent contributors to an actively engaged team.

The now-created psychologically safe space is based on positive interactions and interpersonal relationships built on trust. Shifts in perspectives of the “why” behind the acquisition, a clear framework on how to have those constructive conversations, and keeping the focus on the team’s purpose and better business outcomes have been major shifts in how they function.

When was a time you experienced a sense of not belonging on a team? When have you felt you had lost your voice at the table; afraid to ask what might be considered a dumb question? How did you feel after a decision was made and you never contributed to the solution despite having ideas to share? Those are telltale signs of a space which is not psychologically safe. We deserve better, as human beings in an uncertain world.